Back

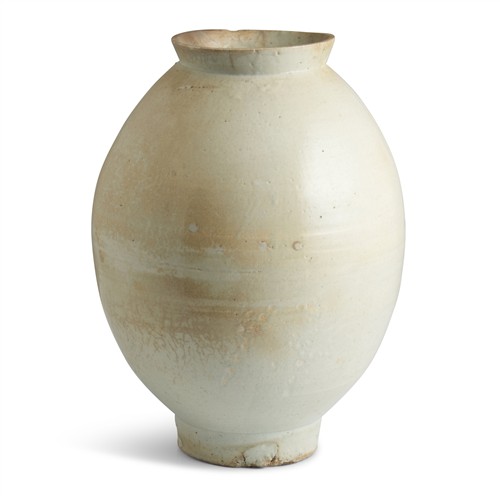

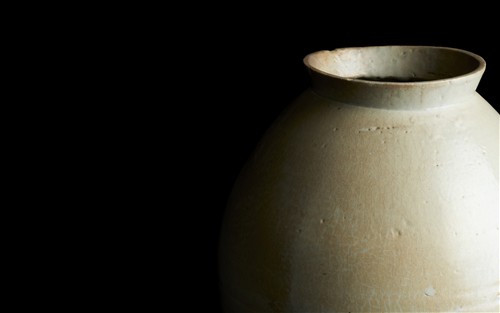

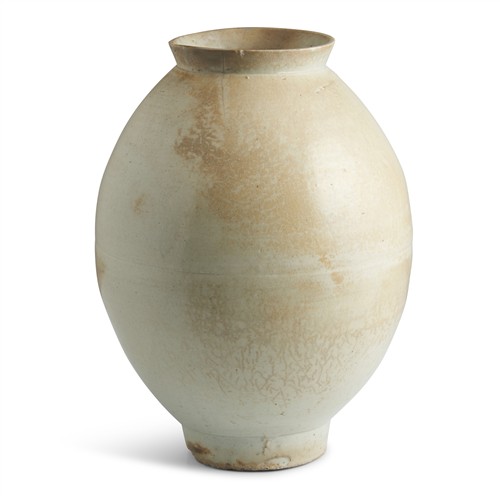

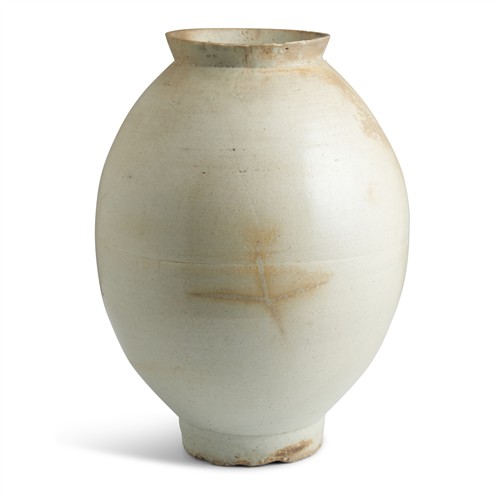

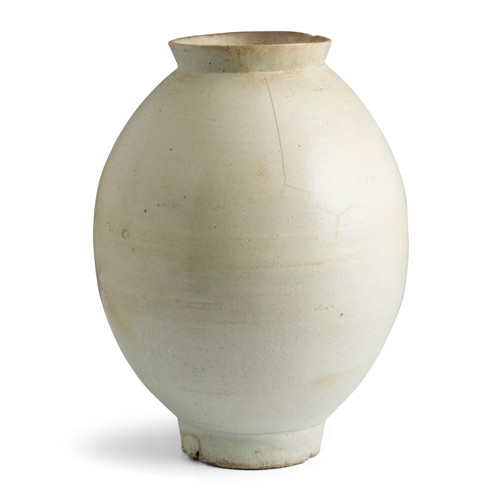

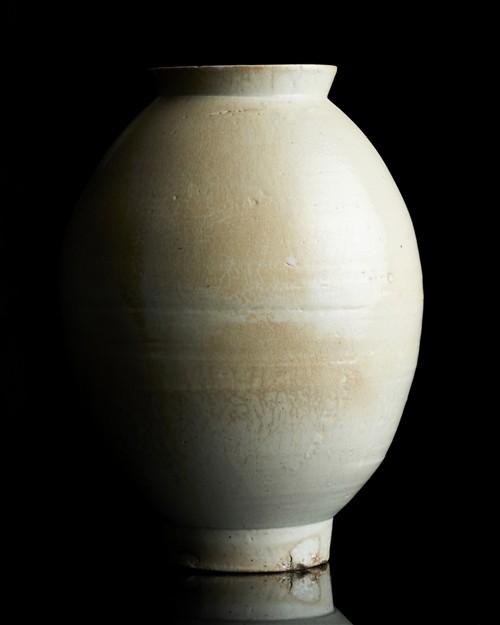

A RARE AND IMPORTANT KOREAN WHITE PORCELAIN MOON JAR, JOSEON DYNASTY, 17TH/18TH CENTURY

The vase is of ovoid form with tall circular foot and everted neck, applied overall with a transparent glaze of blue cast with random pink suffusions and random large craquelure.

韓國 朝鮮王朝十七至十八世紀 月亮罐

37cm high

Unsold

Lot 158A

The vase is of ovoid form with tall circular foot and everted neck, applied overall with a transparent glaze of blue cast with random pink suffusions and random large craquelure.

韓國 朝鮮王朝十七至十八世紀 月亮罐

37cm high

Estimate $15,000 - $25,000

A few areas of re-touch on the mouth rim, a star crack on the body, a thin hairline crack extended from the mouth rim.

CLICK TO SEE DETAIL PHOTOS OF THE WHOLE AUCTION